It's a superficially persuasive argument, which is perhaps why a single payer Medicare for All plan has apparently been declining in public popularity at the same time that a public option has become a more attractive choice in the eyes of the electorate. One might also fault the two main presidential contenders who support Medicare for All—Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren—for doing an inadequate job of rebutting this argument. After all, it appeals to both the all-American notions of freedom and personal choice on the one hand and the left/liberal desire to help the unfortunate on the other. What could be better?

The only small problem (hardly a meaningful one in political campaigns) is that the argument is fraudulent. A public option would not carry the same advantages as Medicare for All, and at the expense of letting people keep their beloved private health insurance plans (rather than cruelly forcing them onto a public plan that would have no copays or deductibles and would cover vision and dental care) would keep the American healthcare system overcomplicated, needlessly expensive, and unequal in fundamentally immoral ways.

Let's examine, for example, Pete Buttigieg's clunkily named "Medicare for All Who Want It." As his campaign website promises, "everyone will be able to opt in to an affordable, comprehensive public alternative." Note the word "affordable," i.e., not free. This already presents a contrast with Medicare for All. Under a single payer plan, getting medical care could become the equivalent of driving on a public road or visiting a public library: no need to worry about picking out a plan that will give you the coverage you need at an affordable price, just take advantage of a service that's free at point of use whenever you need it; all you need to do is pay your taxes. Not so under Medicare of All Who Want It, or public option plans in general. As under the current system, the burden would be on consumers to pick the plan—public or private—that they believe is the most affordable given their circumstances.

This is not the only difference. For instance, as Dylan Scott of Vox notes, "The government plan would cover the same essential health benefits as private plans sold under Obamacare, though the details are left vague on what patients would pay out of pocket." This detail stands in contrast to Medicare for All, which, with its lack of copays and deductibles, "almost eliminates [out-of-pocket spending] entirely."

And what of those who are unable to afford private insurance? Buttigieg's website explains as follows:

The plan will automatically enroll individuals in affordable coverage if they are eligible for it, while those eligible for subsidized coverage will have a simple enrollment option. A backstop fund will reimburse health care providers for unpaid care to patients who are uninsured. Individuals who fall through the cracks will be retroactively enrolled in the public option.So, from the sound of it, those who do not enroll in private insurance (including those who fail to do so for financial reasons) will be "automatically enroll[ed]" in the public option, even "retroactively enrolled" should they "fall through the cracks." Nothing on the website page indicates that private insurance will be made equally as "affordable" as the public plan, meaning that some will, presumably, be forced by their own circumstances to rely on the public option; the sacrosanct ideal of choice will apply only to those who are able to afford private insurance, while those unable to do so will be automatically enrolled in the public alternative (again, going by the sound of it). Details in this regard are scant, however.

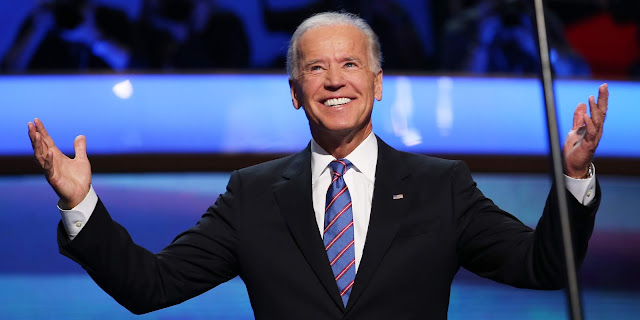

Lest I appear to be singling out only Buttigieg's plan, we should also examine another public option-based healthcare proposal. Let's also take Joe Biden's. Biden's own website is only able to promise that his plan would insure "more than an estimated 97% of Americans"—leaving millions uninsured, in other words. The poor and sick will, apparently, be awarded with the "choice" to remain uninsured, with predictable consequences: People's Policy Project Matt Bruenig estimates that, even assuming the uninsured rate does fall to approximately 3% under Biden's healthcare plan, this could still mean the preventable deaths of 125,000 people in the first ten years after the plan's implementation—deaths that could be avoided under a genuinely universal healthcare plan, such as Medicare for All.

Whatever specific, avoidable flaws the Biden and Buttigieg plans may have, the reality is that all public option plans are doomed to run into the same problems. As George Bohmfalk writes in The Charlotte Observer, a public option "will likely become the insurer of last resort to the sickest and oldest among us. The insurance playing field will be anything but level. As deficient as they are, for-profit insurers will cleverly market themselves to the young and healthy, leaving those who use more healthcare to the public option. Its costs will balloon, dooming it to fail, to the delight of for-profit companies." To be sure, as long as private health insurance companies exist and are forced to compete with a public health insurance, they will use their considerable lobbying influence to weaken and undermine said public option. One can imagine the fate of those forced to rely on a public option as it's progressively slashed and weakened by Republicans (and, in all probability, centrist Democrats) in Congress, under pressure of the private health insurance lobby.

A public option also fails to offer the savings that a single payer plan would. Benjamin Studebaker and Nathan J. Robinson elaborate on this point in an article for Current Affairs:

Single payer systems control costs by giving the health service a monopoly on access to patients, preventing providers from exploiting desperate patients for profit. If instead there are a large number of insurance companies, providers can play those insurance companies off each other. Right now, we have a two-tier system, in which the best doctors and hospitals refuse to provide coverage unless your insurer offers them exorbitantly high rents. To support that cost while still making a profit, your insurer has to subject you to higher premiums, higher co-pays, and higher deductibles. Poor Americans with poor-quality insurance are stuck with providers who don’t provide high enough quality care to make these demands. The best providers keep charging ever higher rents, and the gap between the care they offer and the care the poor receive just keeps growing. Poor Americans are now seeing a decline in life expectancy, in part because they cannot afford to buy insurance that would give them access to the best doctors and hospitals. Costs balloon for rich Americans while the quality of care stagnates for the poor.

The bloat doesn’t just come from providers. Because insurance works on a profit incentive, the insurance companies must extract rents as well. So the patient is paying to ensure not only that their doctor or hospital is highly-compensated, but that the insurance company generates profit too. Each insurance company has its own managers—its own CEO, its own human resources department, and so on. We have to pay all of these people, and because there are so many private insurance companies, there are so many middle managers to pay.In a time where urgent (and necessarily costly) action is required on climate change, allowing vast sums of money to be wasted on bureaucracy and exorbitantly high rates for medical care is particularly obscene.

To be sure, Medicare for All would significantly expand federal spending and require new taxes—as did its namesake Medicare, and Social Security before that. Those two government programs, of course, enjoy overwhelming popularity. According to a study from the libertarian Mercatus Institute, Medicare for All would significantly reduce national spending on healthcare, meaning we would pay less in new taxes than we are currently paying in private insurance premiums, co-pays, deductibles, etc. Those new taxes, furthermore, could be more fairly distributed than private insurance premiums, which (unlike income and payroll taxes) do not take into account the income of the person paying. The end result is that the vast majority of the population would surely end up saving money as a result of single payer healthcare funded by a progressive tax system, even taking into account whatever new taxes it required. The current system distributes costs in a highly regressive fashion. People in the 50th income percentile—squarely in the "middle class," with an annual income around $48,000—pay a total tax rate of 24.7%; the 400 richest people in the country pay a rate of just 23.1%. But if employee contributions to health insurance plans are treated as another form of taxation, the 50th percentile tax rate jumps to 37.6%, while the rate for the top 400 remains effectively unchanged. This doesn't even take into account out-of-pocket costs.

It should be clear, then, that any attempt to present the public option as a plan that would offer the same benefits as Medicare for All, while preserving "choice," is simply dishonest. Fearmongering against single payer healthcare plans by claiming that they would "kick 149 million people off their current health insurance," as Amy Klobuchar recently did, is something even lower. One can, of course, argue that Medicare for All would be virtually impossible to get through Congress. True, but by all indications a public option plan would run into similar opposition from the health insurance lobby. It is not at all clear how settling for a half-measure before any negotiations have even begun—and a half-measure that is still highly unlikely to make it through Congress, at that—is better than pushing for a plan that is both fair and cost-effective. As Libby Watson wrote for Splinter (RIP):

[A public option plan] would obviously be better than what we have now, since what we have now is lethal, toxic sludge. The questions that matter for politicians and advocates when it comes to choosing between a policy that’s merely better and one that’s actually good is whether the good policy is truly out of reach, and whether the worse policy would prevent reaching a better policy goal.As she correctly concludes, a public option would hardly be easier to pass through Congress, and could, if anything, "take[] the wind out of the sails of reform" if passed, making it less likely we would ever have a single-payer plan.

Healthcare is a complicated matter, and one can hardly fault average Americans who are more attracted to a public option and fail to see, at first blush, why it's necessary to for many millions to be "kicked off" of their private insurance plans. In all likelihood, many haven't devoted the time to learn why a public option is a wildly inadequate alternative, and the debates among the Democratic primary candidates have surely done little to illuminate the subject. As for politicians who run for office proposing public option plans over Medicare for All, and using dishonest arguments to support their position, an altogether different—and far less generous—judgment is in order.