|

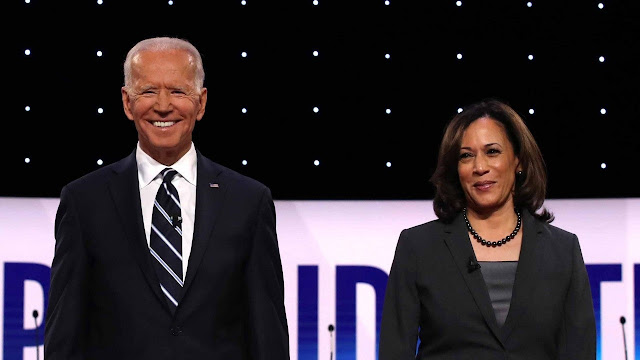

| (MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images) |

Seeing the end of the Trump presidency this past Wednesday felt a bit like waking up after a long and strange fever dream: how much time has passed? Nine hours? Four years? A century? Am I really awake now or is this just some trick my mind is playing on me? Was there ever really a time before Trump was president? Or was that just a dream?

Not to imply it brought any great sense of relief for me. No, as I watched Joe Biden get sworn in as the country's 46th commander-in-chief and heard the paeans to unity and cooperation in his speech, I couldn't help but feel our long national nightmare is far from over. I don't know what "unity" will look like in this moment in history, but I have little optimism about it being the answer to the problems we're all facing — or that old "Uncle Joe" will be the right man to fix them. But I'm not writing this post to make predictions about the next four years, I'm trying to offer some insight about the last four — so we'll table that discussion for later.

What can we say about the Trump presidency, now that it's all said and done? There are the obvious things, of course — that it was a grotesque carnival of incompetence, corruption and cruelty. But many others have remarked, and will continue to remark, on all of this. So why dwell on it? As I said, those are the obvious aspects of the Trump presidency. But perhaps the biggest underdiscussed truth about Trump's term in office is that he was in many ways a remarkably non-transformative president. George W. Bush left office having plunged the country into not one but two new wars, signed the Bill of Rights-shredding USA PATRIOT Act and established the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay where, to this day, "terror suspects" are being indefinitely detained. Ronald Reagan's orgy of deregulation, tax-cutting and union-busting helped reshape the economy in ways we're still living with today. Even the last one-termer, George H.W. Bush, managed to fit in the Gulf War and the invasion of Panama before leaving office, not to mention signing NAFTA. Aside from the tax bill he signed in 2017, what did Trump actually manage to get done? What legacy will he have left even a matter of months from now, when Biden's had time to undo the executive actions he took?

One of the great ironies of the past several years is that, despite the unending focus on Trump himself — whether he was being worshiped by his followers as the savior who will Make America Great Again or vilified by his detractors as a Fascist threat to Our Democracy — he was little more than a vehicle for largely unexceptional Republican policies. While he might have run on a heterodox platform in 2016 and certainly never behaved like a regular politician, to say the least, he mostly governed as exactly what he was: a Republican president.

And an ineffectual one, at that. What the polarized discourse around Trump — the stark divide over whether he was either a godsend or a Nazi monster — obscured was that he was really a weakling all along. Political theorist Corey Robin was one of the ones to consistently get this right:

[Trump's] weakness has been evident from the beginning, as skeptics of the authoritarianism thesis, myself included, have argued. For last the two years, it hasn’t been a Democratic House but a GOP Congress that refused to give Trump money for his wall. Even with total control of the federal government, Trump never got an inch of that wall built. Nor was he able to get any legislation to restrict immigration.

Far from consolidating control over the GOP, much less the polity, Trump and his positions have been consistently rebuffed by the electorate, the Democrats, officials in the Executive branch and other parts of the government, members of his administration — as well as his own party. Indeed, Trump delivered budgets that were rejected not once but twice by a GOP-led Congress, yielding a spending package in 2018, in the words of The Atlantic, that would “make Barack Obama proud.” [hyperlinks in original]

The last few months of his presidency made this clearer than it had ever been, as his attempts to overturn the election results amounted to making a whiny phone call to Georgia election officials and sending Rudy Giuliani to fart in court. The climax of it all came when a Trump-incited mob stormed the Capitol and ultimately succeeded only in convincing a number of congressional Republicans to drop their plans to challenge Biden's electoral college votes.

Obviously, being inept and ineffectual limits a president's ability to do good — but it limits his ability to do harm as well. With this in mind, it's ridiculous to argue Trump might be worst president of all time, or even of this century, at least if one is thinking in terms of the damage caused. As Glenn Greenwald writes,

Those who want to insist that Trump’s evils are unprecedented...should be prepared to explain which acts of Trump’s compete with the destruction of Iraq, or the implementation of a global regime of torture, or the “rendition” kidnappings and CIA black sites and illegal domestic eavesdropping under Bush and Obama, or imprisoning people for decades with no due process, and on and on and on.

Of course, Trump himself was more flagrantly reprehensible than his predecessors, who usually made an effort to project some sort of decent and honorable image. And as a person he is, as I once put it, "defective on every level...moral, intellectual, spiritual, emotional." But judging Trump as a person and Trump as a president are two different matters.

The most truly remarkable — and terrifying — effect that Trump had as president was to markedly increase the level of derangement apparent in American politics. If Nixon was the man who (in Hunter S. Thompson's words) "broke the heart of the American Dream," Trump was the man who broke its brain.

The Right had more than its share of baseless conspiracy theories even before Trump began his campaign in 2015, but the developments since then have been nothing short of astounding. The adherents of QAnon, which casts Trump as the hero fighting against a cabal of Satanic pedophiles, have crafted a mythos as elaborate and unsettling as anything one could find in the writings of H.P. Lovecraft. This isn't a belief confined to hyper-online weirdos, either: the last elections featured "at least a dozen Republican congressional candidates who had endorsed or given credence to [QAnon]," two of whom ended up winning seats in the House of Representatives.

That same derangement was, of course, on full display when the Capitol was stormed earlier this month. Many, if not all, of the people taking part no doubt believed Trump was the rightful winner of the 2020 presidential election — and that, somehow, he really would lead them in a revolution that would overturn Biden's victory. One doesn't have to agree with the more hysterical reactions to this (incredibly stupid and ultimately ineffectual) event to see it as a symptom of what amounts to mass insanity.

But the madness certainly hasn't been confined to the Right. On the contrary, the thought patterns that became widespread among liberals during the Trump years were alarming in their own way. The so-called #Resistance emerged as, in many ways, a liberal equivalent of the Tea Party. Just as Tea Partiers had decried Obama as a Communist tyrant, many liberals spent Trump's presidency claiming that he was a Fascist menace.* And, just as conservatives often seemed to believe that Obama was paradoxically both a diabolical threat to freedom as we know it and also a feckless incompetent, #Resisters could easily swing back and forth between viewing Trump as a blundering doofus and viewing him as a terrifying American Hitler.

Worse than that, though, was the unshakeable obsession with Russia that took hold of countless liberal brains over the past four years. Awkwardly worded ads on Facebook and a spear-phishing scam that fooled John Podesta became an existential threat to American democracy and an act of war by Vladimir Putin. Polling by YouGov in 2018 found that "[t]wo out of three Democrats also claim Russia tampered with vote tallies on Election Day to help the President — something for which there has been no credible evidence." Before his investigation concluded without finding any evidence of coordination between the Trump campaign and Russia, Special Counsel Robert Mueller developed an utterly creepy cult following "complete with T-shirts, scented candles and holiday-themed songs like 'We Wish You a Mueller Christmas.'"

This obsession with Russia quickly turned into an insistence that Trump was governing as a puppet of Vladimir Putin, despite the fact that his foreign policy was, for the most part, that of an unexceptional Republican (which is to say, often diametrically opposed to the Russian government's interests). Even now, after the anticlimactic end of the Mueller investigation, this mania still persists not just among Democratic voters but even among prominent figures in the party. Just this week, Hillary Clinton tweeted that "[Speaker Nancy Pelosi] and I agree: Congress needs to establish an investigative body like the 9/11 Commission to determine Trump's ties to Putin so we can repair the damage to our national security and prevent a puppet from occupying the presidency ever again." Attached to that tweet is a less-than-two-minute video of a conversation between Clinton and Pelosi, in which the Russian president is mentioned by name no less than seven times and more or less blamed for the storming of the Capitol.

.@SpeakerPelosi and I agree:

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) January 18, 2021

Congress needs to establish an investigative body like the 9/11 Commission to determine Trump's ties to Putin so we can repair the damage to our national security and prevent a puppet from occupying the presidency ever again. pic.twitter.com/yR7LQmXm5Z

One of the few things that I allow myself to hope for from the Biden presidency is that at least Donald Trump will no longer be sucking the oxygen out of every political conversation. Even the complacency that seemed to prevail among many liberals during the Obama years is preferable to the hysteria it's often been replaced with under Trump. If "Sleepy Joe" can help the political discourse calm down a little bit then, well, I suppose that's something, at least.

Of course, the shock of Trump's victory and the surreal spectacle of his presidency did help radicalize some left-leaning people, and pushed others who were already politically radical (myself, for example) to get more active in trying to push for a left-wing agenda — probably the best thing to come out of the past four years. We can only hope that Bernie Sanders' defeat in the 2020 primary, and the victory of an utterly Establishment Democratic ticket in the general election, won't completely squelch out this nascent leftist movement — but ultimately that remains to be seen.

So, those were the Trump years. Where do things go from here? God only knows. While I'm hardly overflowing with optimism about President Biden, I can of course only wish him the best when it comes to trying to manage the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic havoc that it's wrought. As for the Republicans, Trump's presidency has put them in a tight spot. At this point, Trump's cult of personality has probably outlived its usefulness for any conservative agenda, but the man still enjoys a high (if somewhat diminished) level of support from the GOP's voters. The bigwigs in the party would probably like to just move on from Trump, embracing his "accomplishments" (the tax bill and his judicial appointments) while putting the more embarrassing parts of his presidency down the memory hole. But it's doubtful that either he or his fans will let them do that.

Of course (as I wrote last year) the 2020 election should also give Democrats plenty of reason to be worried about their future, and hardly marked the stark repudiation of "Trumpism" that many had been hoping for. But, on the other hand, it's certainly questionable whether Republicans will be able to find someone who can replicate Trump's appeal. Trump is a "genuine rustic idiot," as Matt Christman recently said, and that was certainly a big part of what drew people to him — one that his wannabe successors like Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley can't replicate. Trump's specific blend of authentic anti-intellectualism, star power and "political outsider" status was likely what let him and his party outperform expectations in both 2016 and 2020. But there aren't many figures who can offer that same distinctive appeal. That may be a saving grace for the Democratic Party going forward, despite their (all things considered) lackluster performance in 2020.

But that's all speculation. All we know for now is that after finishing his 10,000-year-long term, Donald Trump has finally left office. There are few things, if any, that I will miss about the time when he was in power. Aside from the occasional moments of hilarity he provides, I'm tired of hearing about him, thinking about him — and writing about him. I hope this is the last time I will feel any need to do so.